Machine Translation Weekly 88: Text Segmentation and Multilinguality

With the semester start, it is also time to renew MT Weekly. My new year’s resolution was to make it to 100 issues, so let’s see if I can keep it. Today, I will talk about a paper by my colleagues from LMU Munich that will appear in the Findings of EMNLP 2021 which deals with a perpetual problem of NLP – input text segmentation. The title of the paper is Wine is Not v i n. On the Compatibility of Tokenizations Across Languages and it discusses the role of text subword segmentation in multilingual representation models and shows that different granularity in different languages might be problematic.

Subwords were originally introduced in machine translation where the segmentation incompatibility probably never was a really big deal. BPE segmentation keeps the most frequent words intact. The rarer the words, the more they get split. Because the subwords get fit on parallel training data, the words in the source and the target language occur approximately equally often. Of course, languages with rich morphology will have more forms that are relatively less frequent, but on the other hand, over-segmentation on the morphologically richer side gives the systems a chance to learn something about morphology (which might not be hundred percent true because the segmentation looks very unintuitive at the first glance, but still it works somehow). For some language pairs, it does not work that well, for instance, Chinese and English. In that case, we just use separate vocabularies for source and target and we are done.

The same subword segmentation algorithms are now used in multilingual representations, which are trained on data that is far from being parallel. In this case, the problem of using commensurable segmentation has no escape solution.

The paper starts with an intuition that sounds very natural to me: if the segmentation algorithm makes the character sequence shortened approximately equally in all languages, then everything is going to be fine. As the paper later shows, it is very often not true.

The paper starts by formalizing this intuition. They define the segmentation compression rate as a ratio of how much many times the average number of tokens per vocabulary item decreases compared to the minimum possible vocabulary size. A nice property of this quantity is that it is equal to 1 for character segmentation and decreases with increased vocabulary size. So, is balancing the compression rate a way to better multilinguality? The answer is: sometimes yes, but for most laguage pairs not at all.

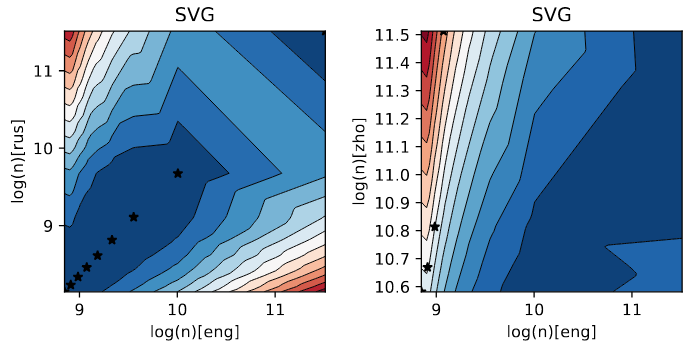

The experiments with bilingual static and contextual bilingual embeddings (trained on tractable corpus sizes, nothing comparable to mBERT or XLM-R) measure how language-neutral the embeddings are with different segmentation. The paper very nicely visualizes the results (I can hardly imagine presenting the results without the visualizations). The following heatmap (Figure 4 of the paper) shows how well the embeddings perform and denote vocabulary sizes with the same compression rate with start. This figure actually the actual findings of the paper (blue is good, red is bad; left English-Russian, right English-Chinese):

When the language typography is similar, having a similar compression rate is good. When the languages are more different from each other, then it gets more complicated, but usually, it seems that a bigger vocabulary pays of in English. The example is for static word embeddings compared using SVG: Singular Value Gap. The evaluation of contextual embeddings using the sentence retrieval task looks similar.

I wonder what that means for the attempts to learn character-level representations and for character-level machine translation. Maybe if we discovered some analytical relations behind these results (the paper only says it is not the compression rate), it could be used to guide the representation learning at the character level, for instance, get an estimate into how many latent states a character sequence should be shrunk. Maybe this is also related to the ideas around information density, so the text would get segmented into units that carry approximately the same amount of information when used in context.

Share the post

@misc{libovicky2021blog1003,

author = "Jindřich Libovický",

title = "Jindřich's Blog -- Machine Translation Weekly 88: Text Segmentation and Multilinguality",

year = "2021",

month = oct,

url = "https://jlibovicky.github.io/2021/10/03/MT-Weekly-Segmentation-and-Multilinguality",

note = "Online, Accessed: 02.04. 2025"

}