Machine Translation Weekly 16: Hybrid character-level and word-level machine translation

One of the topics I am currently dealing with in my research is character-level modeling for neural machine translation. Therefore, I was glad to see a paper that appeared on arXiv last week called On the Importance of Word Boundaries in Character-level Neural Machine Translation that shows an interesting hybrid between word-level and character-level models.

At first sight, it may seem that using words is a natural choice—after all human dictionaries consist almost exclusively of word-to-word translations. One of the problems is that the current models can only work with a limited vocabulary (tens of thousands of entries). This is not much if you consider that in inflective languages each word can occur in many forms. Even if we were able to use much larger vocabulary (say one million word forms), most of the word forms would appear so scarcely in the training data, that it would be hardly possible to learn anything useful about them. Also, defining what a word becomes tricky when you need a formal definition. In many languages, splitting text into words is not a simple task at all. It is not only Chinese that does use spaces between words, but similar issues can also appear with long German compounds or in agglutinative languages (like Finnish or Turkish) where one word can correspond to an entire phrase in languages like English.

Let’s take a sentence (from WMT13 test data):

However, the Brennan Centre considers this a myth, stating that electoral

fraud is rarer in the United States than the number of people killed by

lightning.

This is how an English a word-segmented sentence would like as an input to a word-based translator. Punctuation is processed separately from the words, and word Brennan ended up out of 40k vocabulary.

However , the <unk> Centre considers this a myth , stating that electoral

fraud is rarer in the United States than the number of people killed by

lightning .

Character-level modeling can potentially solve these issues, but it has its own problems. Word level models can store a lot of information about the word usage in the embedding matrix. How a word is used has usually little to do with how it is spelled. Therefore, in character-level models, this information cannot be stored in the embeddings and must be resolved in the later layers that combine the characters together. In some sense, we are forcing the network to learn much more complicated functions of the input than in word-level models. In word-level models, many “irregularities” can be stored in the embeddings. In character-level models, everything needs to be resolved in the later hidden layers. Moreover, character sequences are much longer than word sequences which makes the character-level models slower.

H o w e v e r , ▁ t h e ▁ B r e n n a n ▁ C e n t r e ▁ c o n s i d e r s ▁ t h

i s ▁ a ▁ m y t h , ▁ s t a t i n g ▁ t h a t ▁ e l e c t o r a l ▁ f r a u d ▁

i s ▁ r a r e r ▁ i n ▁ t h e ▁ U n i t e d ▁ S t a t e s ▁ t h a n ▁ t h e ▁ n

u m b e r ▁ o f ▁ p e o p l e ▁ k i l l e d ▁ b y ▁ l i g h t n i n g .

The state-of-the-art models use a segmentation into so-called sub-word units. When using the sub-words, frequent words (which are also those which are the most irregularly used) are kept in the vocabulary intact, less frequent words get split into smaller segments which can go down to separate characters. The least frequent words which get split into characters are often names which are not usually translated anyway, so the segmentation allows easy copying or transliteration which would be difficult to learn on the word-level. The problem of the sub-words is that it is precomputed using some heuristic statistics that are totally unrelated to the translation model. It is not clear if the segmentation suits the model the best.

Sub-word segmented sentence can look like this. The @@ sign serves as an

indicator that the sub-word should be connected to the following one.

However , the Brenn@@ an Centre considers this a my@@ th , stating that

electoral fraud is r@@ ar@@ er in the United States than the number of people

killed by ligh@@ tn@@ ing .

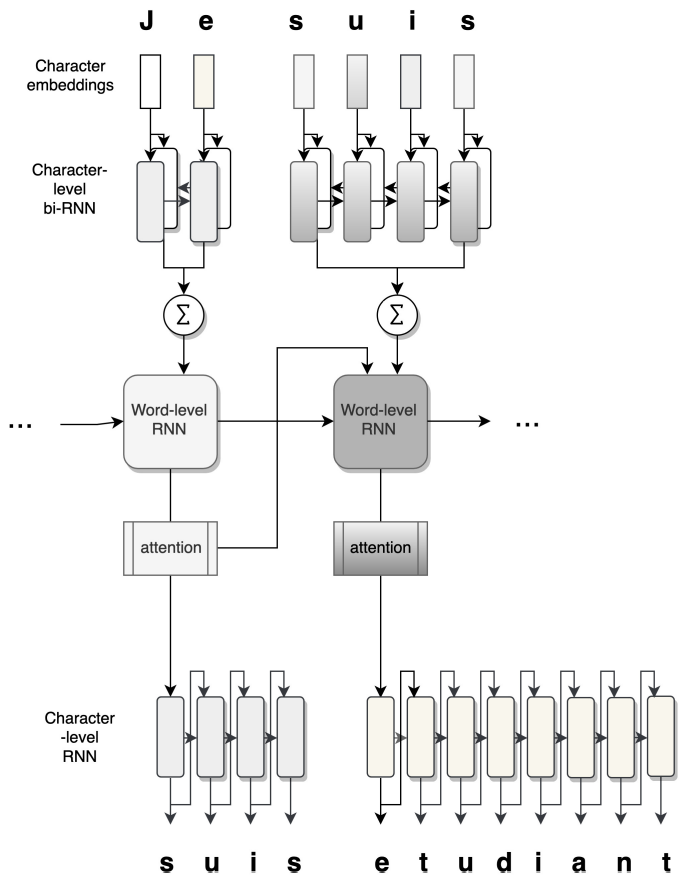

The paper I would like to discuss today presents an alternative way of how to treat the input and output. The text is still split into words, but the words are processed separately on the character level. It is pretty straightforward on the encoder side. Characters of every word are processed with a “small” recurrent network and the output of this “small” encoder is fed in the “large” encoder, in the same way as word embeddings usually are.

The tricky part is the decoder. In each step, the decoder receives the embedding of the previous words (or a different unit) and based on that word and the previous ones, it is supposed to predict what word will follow. For the previous word, we can do the same thing as in the case of the encoder. Now, we have the decoder state and instead of a single symbol, we are supposed to generate a sequence of characters. How can we do that? It is surprisingly easy—we can run a “small” recurrent decoder that will generate the word character by character. And this is the whole idea of the paper. The authors illustrated that on a (sad and gray) picture on page 3 of the paper:

The results in terms of translation quality are decent. Long story short: if you use recurrent networks, it does not really matter if you used sub-word units or this hybrid approach. For languages with rich inflection, it seems to perform better than subwords and sometimes better than characters. Unfortunately, the authors do not show how this idea would with the Transformer model, which is the architecture that currently delivers the best translation quality. The reason might be that unlike recurrent networks, training a character-level Transformer is not an easy task at all, although I believe that it would work well in this hybrid setup.

They also evaluated their German model using Morpheval, a dataset that consists of small test sets targeted on specific morphological phenomena. (I am glad that someone finally reports more than just plain BLEU scores.) The hierarchical model does a surprisingly good job in capturing agreement in morphological categories (especially grammatical gender).

To my surprise, it is much worse than subword-based models for translation of German compounds (Rechtsschutzversicherungsgesellschaften!) than sub-word models. This, in my opinion, shows that the flaw is in the tokenization rather than in the modeling part. Maybe it got better if we used the hierarchical model on the sub-words that apparently can split the compounds in a meaningful way. Or, of course, it would be best if we could learn the segmentation end-to-end with the translation model. I believe this architecture is an important step in this direction (although I am not sure if this is what the authors of the paper think as well).

BibTeX Reference

@misc{ataman2019importance,

title={On the Importance of Word Boundaries in Character-level Neural Machine Translation},

author={Duygu Ataman and Orhan Firat and Mattia A. Di Gangi and Marcello Federico and Alexandra Birch},

year={2019},

eprint={1910.06753},

archivePrefix={arXiv},

primaryClass={cs.CL}

}

Share the post

@misc{libovicky2019blog1023,

author = "Jindřich Libovický",

title = "Jindřich's Blog -- Machine Translation Weekly 16: Hybrid character-level and word-level machine translation",

year = "2019",

month = oct,

url = "https://jlibovicky.github.io/2019/10/23/MT-Weekly-Character-Word-Level-MT",

note = "Online, Accessed: 02.04. 2025"

}