Machine Translation Weekly 51: Machine Translation without Embeddings

Over the few years when neural models are the state of the art in machine translation, the architectures got quite standardized. There is a vocabulary of several thousand discrete input/output units. As the first step, the inputs are represented by static embeddings which get encoded into a contextualized vector representation. It is used as a sort of working memory by the decoder that typically has a similar architecture as the decoder that generates the output left-to-right. In most cases, the input and output vocabularies are the same, so the same embedding matrix can be used both in the encoder, in the decoder, and also as an output projection giving a probability distribution over the output words.

Indeed, they are different underlying architectures (recurrent networks, convolutional networks, Transformers), people try to come up with conceptual alternatives such as non-autoregressive models or insertion-based model. However, there is not much discussion about when the initial embedding layer is really necessary and when not. This is the question that a recent pre-print Neural Machine Translation without Embeddings from the Tel Aviv University attempts to answer.

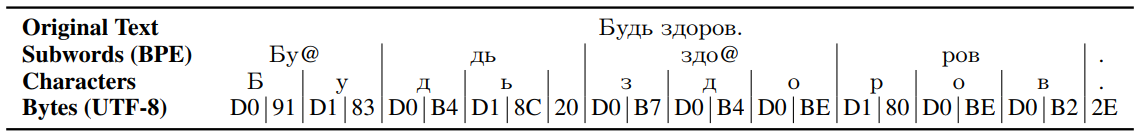

The paper presents a series of relatively simple experiments. They trained translation systems with the standard architecture with subword input, character inputs, and byte inputs. In an ASCII world, characters would be the same as bytes, but with Unicode, characters might consist of multiple bytes (my impression is that the more non-western the alphabet is, the more bytes are required for a character). As a contrastive experiment, they trained a byte-based model without embeddings, i.e., the input represented as one-hot vectors.

It is nicely shown in Figure 1 of the paper:

Let us discuss what omitting embeddings really means. The one-hot vector that is on the input gets multiplied by some weight matrices—which means it gets embedded anyway. In the Transformer architecture, the encoder starts with a self-attentive sub-layer, so we can view it as having three different embeddings for each byte: one for attention queries, one for attention keys, and one for attention values (that get further split for individual heads). With a subword vocabulary with tens of thousands of units, this would mean a considerable increase in parameter count, after all the embedding matrix is one of the biggest parameters of the models. There are only 256 possible byte values, not having the embedding layer hardly affects the total number of parameters. The quantitative results show that when translating from English, the non-embedding byte-level model performs on par with sub-word models.

The paper shows an intuitively clear fact, but it is nice to have this intuition confirmed experimentally. The embeddings are not a magical component the NMT model cannot work without. The role of embeddings is mainly reducing the number of parameters (and thus also being able to learn something about less frequent tokens). At the top of the Transformer encoder, we need to represent the input for queries, keys, and values in the self-attention heads. With the embedding layer, we assume, this can be decomposed into two matrices: one “general” word representation and one the task-specific projection in the first layer. (With the RNN models we can about different representations for different gates fo the cell.)

Under such an interpretation, I am a little bit confused about the conclusions of the paper. There is a discussion about some sort of meaning orthogonality of the bytes which allows them to get rid of the embeddings. I am not sure if this is the right view: they still multiply one-hot representation by a weight matrices, so technical, they do embed the inputs, but differently for different self-attention components.

Also, the results they present do not agree with what I got when I experimented with character-level models on WMT data and this year’s ACL papers on char-level models that show that there is still a gap between subword models and character models. This gap seems not to exist in the baseline experiments in this paper. I am quite curious what is the secret ingredient that causes that. However, it might be a difference between WTM and IWSLT datasets.

Share the post

@misc{libovicky2020blog0903,

author = "Jindřich Libovický",

title = "Jindřich's Blog -- Machine Translation Weekly 51: Machine Translation without Embeddings",

year = "2020",

month = sep,

url = "https://jlibovicky.github.io/2020/09/03/MT-Weekly-Machine-Translation-without-Embeddings",

note = "Online, Accessed: 08.04. 2024"

}